Translation:

1 : an act, process, or instance of translating: as a : a rendering from one language into another; also : the product of such a rendering

Translations is an appropriate name for the play in that a translation of something is not merely a renaming, but it is a reinterpretation of a word or words. This is exactly what the Owen and the British soldiers are doing. They are recreating something new out of something old. In reinterpreting something, the original will be lost, but the hope is that an essence of it will still remain. The British soldiers pay no attention to this at all, except for Yolland. Their only worry is to entirely Anglicize place names. Any Gaelic essence left is irrelevant to them. The original names most likely contain natures that cannot be translated and do the originals no justice. Therefore, the reconstruction—or the translation—of something is not completely real; something has been altered and will probably never resurface.

Monday, November 30, 2009

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

Fork in the Road

I find that Lucy's quest for identity is much like Omishto's. Both struggle between two entirely different settings. I chose to include a picture of a road split because it resembles their choices in their lives. Lucy's stuck between America and her homeland, Antigua, while Omishto's being pulled between modern society and her native heritage.

Mother figures are very important for both stories. It's funny how neither Lucy's mom nor Omishto's are main characters, but their presence remain with the girls forever. Lucy's mom provides a connection to her past in which she desperately tries to escape. Omishto's mother serves as her link into modern society and her potential future. The two also have other key influences in their lives, being Mariah and Ama. Their presence serves as a way for the girls to question their surroundings with what they know and what they don't know. Both girls want what the other has. Lucy looks for new experiences while Omishto searches for her roots to decide what path is best to take. That's where the two are different. Lucy made up her mind in the beginning to travel to a new land and almost forces herself to become a new person. Omishto's approach was far different. She observes rather than taking action. She finds Ama and her own Taiga heritage incredibly interesting and "watches" Ama and looks for reasons behind her actions. The panther's death and the two courts she attends symbolize the choices she has to make in her life.

Both girls are at an age in their lives where decisions they make now will forever effect their futures. Lucy must either make amends with her mother and accept her past or hold her peace and move on. Omishto has the choice to follow her mother or Ama who now has been banished from the tribe. This is a crucial moment for her, since Ama is no longer around, Omishto sees the tribe is at danger of disappearing like the panther.

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

POWER

Linda Hogan’s novel, Power, presents two different ways of perceiving the world from a couple female perspectives. The beauty of this novel is that it reveals the similarities and differences, uncovering the dangers in both and the ways in which power is used within both belief systems, for good and bad purposes. The story starts off very strong, with the storm scene and the climax of the panther’s death. I found this section very powerful and expressive.

“She. She has always watched for it. She has always believed it is there. Sometimes at night she has looked out into the darkness and seen its eyes. They have exchanged glances.” (57)

Ama is in complete control of her destiny, her actions directed toward bringing Omishto into the clan. Omishto finally connects the dots and realizes that Ama knows what she’s doing even if the panther is endangered. The sick panther represents the death of the old ways of the clan as Omishto represents their future. The language flows so well here, I felt embedded with the story. The world is portrayed here as hostile, not literally, but through the language. A split occurs after the initial storm scene. I feel that the remainder of the novel consists of Omishto’s journey to settle this schism and more importantly to understand it and where she belongs within it. Power in this novel is represented by the storm, the clan, and feminist power, in which Omishto’s power has potential in both worlds.

“She. She has always watched for it. She has always believed it is there. Sometimes at night she has looked out into the darkness and seen its eyes. They have exchanged glances.” (57)

Ama is in complete control of her destiny, her actions directed toward bringing Omishto into the clan. Omishto finally connects the dots and realizes that Ama knows what she’s doing even if the panther is endangered. The sick panther represents the death of the old ways of the clan as Omishto represents their future. The language flows so well here, I felt embedded with the story. The world is portrayed here as hostile, not literally, but through the language. A split occurs after the initial storm scene. I feel that the remainder of the novel consists of Omishto’s journey to settle this schism and more importantly to understand it and where she belongs within it. Power in this novel is represented by the storm, the clan, and feminist power, in which Omishto’s power has potential in both worlds.

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

NAMES

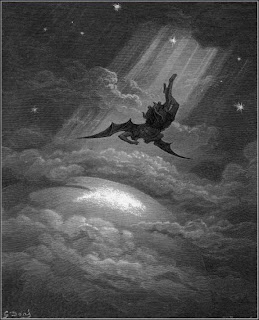

Names take a powerful role in this novel. Lucy understands that her name symbolizes important characteristics of her own identity. Her last name, Potter, shows an influence of colonialism that she figures is from an English slaveholder. Lucy cannot stand how her mother ignores her dreams and expects only her brothers to attend college and for Lucy to simply become a nurse. Her middle name, Josephine, hints at this low expectation her mother has for her. It comes from a rich uncle of Lucy’s that died broke and lived in a tomb. Her first name, Lucy, has the worst meaning, deriving directly from the devil himself, Lucifer.

I chose to include an image of Lucifer because I really like the reference to Paradise Lost by Milton. The triumph of good over evil is very clear, but the way Lucifer is seen as sympathetic in his quest to be free from God’s control relates to Lucy’s struggle of rejecting morals. God’s morals are good, clearly, and do not need to be challenged. Setting one’s own path comes from human experiences. Lucy obviously despises most cultural norms out of the pride that people see in Lucifer. It is not clear either that Lucy strives to find new norms for herself as she searches for her new identity.

“I understood that I was inventing myself… I could not count on precision or calculation; I could only count on intuition. I did not have anything exactly in mind, but when the picture was complete I would know” (134).

Lucy constantly contradicts herself throughout the entire novel. She wants to be free and love her new self but, to her, that would only mean she is not free at all. Eventually drastic freedom must let itself become real, life commitments. Lucy is hesitant at this idea. The way Lucy perceives her past as being “[a] person you no longer are, the situations you are no longer in" is completely untrue (137). Her past is what causes her to undergo such a difficult transition. After she frees herself from her past attachments, she now longs for “[loving] someone so much [she] would die from it” (164).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)